Everything posted by gildone

-

Ohio Intercity Rail (3C+D Line, etc)

We need to revive the Lakeshore Corridor Rail Initiative: http://www.lakeshoretrain.org/

-

Freight Railroads

I'm sure Amtrak wouldn't want to have any additional costs with regard the lakefront track. They have been foisting NEC costs off onto the national network for so long that they wholeheartedly believe their bogus route cost accounting numbers about the long distance trains. I can't see them wanting to take on any additional track maintenance responsibility outside the NEC. The 10 miles of track they own just west of Albany for the Lake Shore Limited to connect to the CSX line into Boston isn't maintained very well. They wanted to kill the Southwest Chief so they wouldn't have to maintain the Raton Pass line that BNSF no longer needs, even though they would have only had to pay a small portion of the costs. Either we force Amtrak's hand on their route cost accounting or we need to split the company in two, with an NEC company that gets Amtrak's current management and a company with new management to take on the rest of the system.

-

Freight Railroads

Didn't you have a bypass plan that NS was mildly interested in several years back? I know NS would never pay for it, but your plan was workable.

-

Amtrak & Federal: Passenger Rail News

Of course, the equipment on the rest of the system, especially the long distance trains, is falling apart. The "old" Acela trainsets are only 20 years old. On the rest of the system, it's 30 or 40 years old. Amtrak would probably argue that the NEC has higher ridership than the national system (and falsely claim that it's profitable)hence that's why they get new equipment, but ridership is not the standard output metric for the intercity passenger industry. Amtrak likes to use the ridership" figure to try to paint the NEC in the best possible light and the interstate/long distance trains in the worst possible light. However, if you were to use the ridership figure on the NEC as Amtrak's percent of total ridership on the NEC, it would be 6%. 94% of the ridership on the corridor is provided by commuter agencies. That begs the question, how important is Amtrak on the NEC then? In reality, the standard performance metric in the passenger transportation industry to measure output is passenger-miles. In that context, the interstate/long distance trains provide the most output. Measuring ridership is akin to Walmart only measuring how many people enter their stores, but that doesn't measure the output of their stores. Average spending per customer measures output. If you look at Amtrak's performance reports they provide total passenger miles for the whole system, but they don't break passenger miles down by business unit (NEC, State Supported, Long Distance). What they break down by business unit is ridership. Another thing to consider: Wikipedia calls Amtrak: "a passenger railroad service that provides medium and long-distance intercity service in the contiguous United States and to nine Canadian cities.' Amtrak would agree with that definition, so exactly how much intercity transportation does Amtrak actually provide on the NEC? The USDOT definition of intercity trips is "non-recurring trips over 100 miles". By that definition about half of all NEC Amtrak passengers. The rest are commuters primarily traveling somewhere along the 94-mile segment between Philadelphia and New York. So why am I bothering to bring this up? Because of Amtrak's management's NEC-centric mentality. Between their bogus route cost accounting system that overstates the cost of the long distance trains by at least $311 million per year (per RPA's report which I posted the summary of further up this thread) and covers up over $1 billion in annual operating losses on the NEC, and deliberately avoiding the use of the standard output metric for their industry, it's apparent that Amtrak deliberately misleading Congress and the American public about to support the false narrative that the NEC is profitable and their strongest business segment. As long as that false narrative holds, it makes it look passenger rail in the rest of the country, especially on the long distance trains, is not worth the investment.

-

Other States: Passenger Rail News

It's downtown, but being under a bunch of highway ramps doesn't mean it's a good location, though I understand why they thought it would be a good idea. We've done a lot of things that seem like a good idea the time, but they turn out to be not so great at some point in the future.

-

Ohio Intercity Rail (3C+D Line, etc)

As far as Amtrak goes, it is my view that their management is un-fixable. They are too NEC-centric and too much believe the garbage their route cost accounting system turns out. I think a necessary fix is to split up Amtrak into two separate companies. Amtrak becomes a NEC-only company. A separate company is chartered and headquartered in Chicago to operate the interstate/long distance network and the state-supported corridors. It's not a far-fetched idea: A Two-Amtrak Concept Railway Age October 10, 2019 https://www.railwayage.com/passenger/intercity/a-two-amtrak-concept/

-

Ohio Intercity Rail (3C+D Line, etc)

The younger generations do want trains. That's pretty clearly known. It's our government that's the problem. I agree about a national plan. A federal passenger rail program is needed (Amtrak is not a rail program). For that we need a federal passenger rail development agency/administration and a dedicated source of funding to purchase rights-of-way, whether it's unused ROW along existing freight mains, abandoned ROW where it makes sense, or new ROW where it's needed. The state of Virginia has a model for this, so there is no need to re-invent the wheel. Also, Amtrak needs to be kept out of the picture as much as possible when it comes to planning. They are too opaque about costs, exaggerate the costs of routes outside the NEC, lie about NEC profitability, and as an increasing number of states are realizing, they are just a bad business partner.

-

Amtrak & Federal: Passenger Rail News

It's been in various business publications in recent months. The pandemic has given companies the opportunity to figure out how to conduct business with less travel. It's working better than they thought, so in addition to the analysis mentioned in this article, the business community itself has been saying that they will be traveling less even when it's over.

-

Cuyahoga Valley Scenic Railroad

Funny, on the desktop it's just a link. Via my phone the Twitter post is visible.

-

Great Lakes Shipping News

I only read the threads in the transportation forum and didn't see it it here where it seemed to make sense to post.

-

Amtrak & Federal: Passenger Rail News

Permanent decline in business travel, the bread and butter of Acela service: Guesses aside, a look at data suggests between 19% and 36% of all air trips are likely to be lost, based on a business-travel analysis I worked on with three airline-industry veterans. https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-covid-pandemic-could-cut-business-travel-by-36permanently-11606830490 Yet Amtrak still sees its future in Acela and the NEC despite the fact that the long distance/interstate trains are bringing in more revenue during the pandemic.

-

Great Lakes Shipping News

Cleveland Cliffs buys ArcelorMittal US and AK Steel: http://www.clevelandcliffs.com/English/news-center/news-releases/news-releases-details/2020/Cleveland-Cliffs-Inc.-to-Acquire-ArcelorMittal-USA/default.aspx

-

Cuyahoga Valley Scenic Railroad

The link is broken. What did it say?

-

Ohio Intercity Rail (3C+D Line, etc)

I don't blame you! I don't know why I'm allowing myself to be sucked back in...

-

Ohio Intercity Rail (3C+D Line, etc)

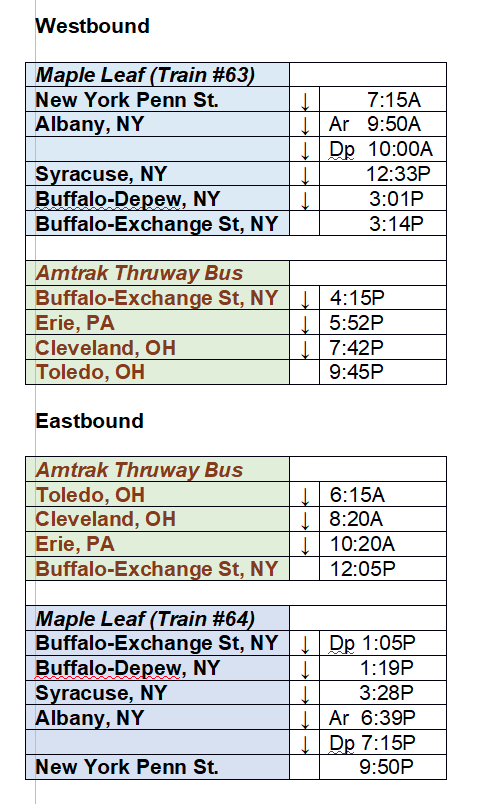

Read the Lakeshore Corridor Initiative. Three additional frequencies along the current Lakeshore Limited route IS the ultimate goal. As for infrastructure upgrades, it won't be that easy. Congestion between Hammond/Whiting and Chicago has been problematic for years. The South-of-the-Lake Bypass is needed to alleviate the problem. That's an expensive project. Also, NS has required that for any new passenger rail services on their lines, all stations have access to both main tracks or be able to be serviced off the mains altogether. That means there can be no new trains serving Bryan, Sandusky, and Elyria unless that occurs. Now, that doesn't mean that new services have to stop in those towns right away, but those changes will ultimately need to be done. Additional frequencies in New York will require, at a minimum, infrastructure investment to eliminate congestion issues between Rochester and Buffalo. Anyway, here's a guesstimate of what a thruway bus to the Maple Leaf could look like. I'm not sure how much layover time Amtrak requires for one of their connecting buses, so I guessed one hour. It could be more. I suggest the new Buffalo Exchange St. Station as the connection point because the Depew Station has a godawful waiting environment:

-

Peak Oil

"That is because yes, we can switch almost everything out to electric vehicles (not everything, but the vast majority, which is enough to make the consumption rate of oil sustainable for a very long time for everything else that still uses it). I have been driving proof of that since 2018, in my Tesla, and I will never buy a gasoline car again... And that, plus the dramatic decline in solar power pricing, changes a great deal about the sustainability of suburban development, too, to your point about us allegedly adapting poorly by continuing to build car-centric development" Just because you and several thousand others are able to drive a Tesla today in no way, shape, or form proves that we will be available to run "the vast majority" of the 273 million or so ICE vehicles in the US on batteries. Not to mention two and three thousand mile produce from California, warehouses on wheels, 12,000 mile supply lines to China, etc. You really don't seem to understand how net energy/energy density. Net energy has been on the decline for decades now. The energy return on oil used to be 100:1. Now it's 17:1 to 30:1 depending upon who you read, but in either case, substantially lower than it used to be and still declining. Solar energy offers about a 7:1 to 9:1, depending upon the source your read. Wind is better at 15:1 to 18:1. Biofuels are under 5:1, except for sugar cane ethanol which is 8:1 to 10:1. Declining net energy means we're already expending more energy to get the energy we need to run society than we used to. The rate of economic growth is tied to the growth in energy production. I read somewhere, but can't recall where, that a 1% increase in GDP requires growth in energy production of 0.9% or 0.95%. As net energy declines, it chews away at the ability to grow the amount of energy available for economic activity. Efficiency improvements can help offset that, but there are limits to that over time as diminishing returns eventually set in. We've had some good advances in energy efficiency in recent years with things like LED lighting, and there more that can be done with changes in home and building design probably being one the biggest. But net energy decline is still on-going and ticking away in the background. Long story short: the only future available to us in terms of energy (unless we figure out fusion, but fusion has always been 30-years away ever since I was a kid) is one of less total energy available. That means some things are going to have to give, and the massive amount of car use in the US is probably one of them.

-

Ohio Intercity Rail (3C+D Line, etc)

An incremental approach to implementing the Lakeshore Corridor Initiative (see link below) could be one way to bring daytime passenger trains to northern Ohio: https://www.hsrail.org/sites/default/files/images/Lakeshore_4_Pager.pdf This would have to occur post-pandemic, of course, but It could begin with a connecting bus from Toledo and Cleveland to Buffalo that would connect with Amtrak's Maple Leaf to New York City. And one from Cleveland and Toledo to connect with a Wolverine Corridor train. This would give Cleveland and Toledo a daytime connection to Amtrak trains to Chicago and New York. From there, piggy back on the Toledo-Detroit Corridor (https://tmacog.org/transportation/passenger-rail) and upgrade to Cleveland-Buffalo and Cleveland-Detroit trains. From there, move on to additional frequencies between Chicago and New York. And what about Ohio's schizophrenic state government when it comes to passenger rail support? Well, one possibility could be to form a joint powers authority made up of local government entities from Toledo, Sandusky, Elyria, Cleveland, and possibly Lake County modeled after the joint powers authorities in California that oversee the Amtrak corridors within the state. As I recall, All Aboard Ohio started looking into this option after former Governor Kasich killed the 3C project, and they found that there doesn't appear to be any legal impediment in the state for local governments to form such an arrangement. This needs looking into again and in more depth, but it's an option. A joint powers authority could apply for federal transportation funds and not involve the state at all if the state is not interested. Money can also be raised for the trains by using tax increment financing (TIFs) from re-development around stations. All of the aforementioned cities have development opportunities around potential station sites.

-

Ohio Intercity Rail (3C+D Line, etc)

Yet when the Ohio Hub plan was being put together, the ridership analysis showed the system to be very much viable. Ridership analyses are very carefully done and designed to be conservative. It's why virtually every state-funded Amtrak corridor in the country exceeded their ridership projections when the trains went into service. No public official wants to be caught supporting a lemon, so the analyses are deliberately designed to be conservative.

-

Ohio Intercity Rail (3C+D Line, etc)

Two considerations: 1) Going through Ohio without stopping is not as workable of a solution as you might think. All those train miles through Ohio have a cost and not stopping in Ohio just puts those costs on surrounding states. That makes the train a less viable idea overall. The Downeaster corridor from Portland, ME to Boston, MA has this problem with New Hampshire. New Hampshire refuses to contribute to the corridor's cost. However, the New England Passenger Rail Authority knows that if they don't make stops in New Hampshire, the financial performance of the train plummets. This leads me to consideration #2: interstate routes should be a federal responsibility. It is a form of interstate commerce after all, but that's a separate subject for another time.

-

Peak Oil

Like I said, we can agree to disagree. The way I see it, we have been doing a lousy job of adapting. We keep building more highways. We keep underfunding transit and failing to modernize and expand our passenger rail system. VMTs continued to go up for the past decade, the covid pause notwithstanding (though the significant increase in teleworking could really help going forward. It has significantly cut my gasoline bil!). We are still constructing homes and buildings that fall way short of the energy efficiency that current technology is capable of (and without undue expense). We are still mandating in the vast majority of the country the construction of energy-inefficient, car-centric living arrangements. If you think we can just switch everything out to electric vehicles and run things at or near the same level we've been running them, then you really don't understand the point about energy density and declining net energy. Did you really read Heinberg's piece? 😉 : Those forecasters were partly right and partly wrong. Conventional oil production did plateau starting in 2005, and oil prices soared in 2007, helping trigger the Great Recession. Afterward, however, there was strong growth in production of >unconventional oil from deepwater wells and Canadian oil sands, and especially from tight oil (also referred to as shale oil) extracted by horizontal drilling and fracking. AND Even though early peak oilers underestimated the rise of unconventional oil through the “magic” of easy credit, and thus miscalculated the timing of maximum overall production, they did improve the public’s energy literacy with two key observations... I followed the discussions pretty closely for well over a decade. The conversation was, in fact, about conventional oil. It may not have been spoken explicitly very often, but the production data that was being analyzed and discussed (at times in excruciating and mind-numbing detail) at The Oil Drum website and elsewhere was conventional production. Unconventional oil wasn't as much on their minds because it was thought that the high cost of exploiting the increasingly low-quality resources that unconventional oil represents would limit its role in global production. The magic of easy credit, brought about in part by the Fed's quantitative easing, and in part by overly-rosy financial projections by the drillers and others in the industry as it sought investors wasn't a logical conclusion to make at the time. Just after the '08 meltdown, it was a more logical conclusion that creditors and investors would be much more cautious. Thus it was thought that unconventional oil would play a minor role. That's why the peak oil crowd (including me) missed that. But there is more: the US Energy Information Administration kept issuing overly rosy production estimates for tight oil (and tight gas) that were consistently above what actually ended up occurring as the fracking decade went on. The number of times the US EIA had to walk back it's projections became laughable for a period of time. At one point and they got so desperate to extricate themselves from corner they backed themselves in that they actually said in a public statement: "Our projections aren't forecasts". Still, the US EIA is looked at by Wall Street and policymakers as a voice of authority, and that likely played a role in investor confidence. So yes, they missed it. I missed it. But let's look at how things turned out: more than half of the industry was in the red from the beginning and remained so. Rex Tillerson, when he was still Exxon CEO, talked about it years ago. Had "the magic of easy credit" not existed, it's debatable how much fracking oil development would have actually occurred and where we would be now. It surprised a lot of people, including me, how long the financial woes of the industry were ignored and how much good money kept being thrown after bad. The Fed is now bailing them out. What do you think this means for the fracking industry going forward? We're going to find out. Gramarye said: ... I just don't see why you can still have confidence in the notion that peak oil deserves any significant place in policymaking or future planning discussions. Because the underlying problems haven't gone away. The way I see it, the fracking bubble allowed us to paper over things for awhile and largely continue business as usual. But it doesn't change the reality of declining resource quality of unconventional oil and declining net energy. It doesn't change the long-running, abysmal financials of the fracking industry. I don't know specifically where things are going to go from here, but neither does anyone else. It's easy to play Monday morning quarterback and try to claim the peak oil crowd completely discredited itself, but that's a myopic viewpoint. Today, I've tried to point out many of the nuances involved and haven't gone away. We see things differently and that's fine. I'll continue to comment here, but there is probably no point in the two of us conversing on the subject much longer.

-

Peak Oil

We can agree to disagree on relevance. A few additional points: – The price rise from 1998 to 2008 was only one act as this has been playing out. – Declining production is only one aspect of the overall issue (See the full Richard Heinberg piece that I posted the link to above). – Your view that we can simply switch out renewables and electric cars for oil and ICE cars misses an important point, because it assumes that renewables offer us similar energy density and energy returned on energy invested (EROEI) as oil. They don't. – The EROEI issue is leads us to the issue of net energy, because as EROEI declines (and it has been declining for far longer than we realize), so does the net energy available for productive use in the economy (It's best if you can look into the EROEI issue and how it inter-plays with the economy yourself). Bottom line: peak oil does not have to result in permanently high prices to be problematic, and the problems don't always have to be sudden or immediately catastrophic. That said, we continue to experience problems related to peak oil: declining net energy, increasing reliance on debt (both public and private) to finance economic growth. Energy growth is key to growing the economy and net energy growth is lagging. In 2018 Bloomberg reported that since the 2008 financial crash, debt has grown at twice the rate of GDP (https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-04-10/global-debt-jumped-to-record-237-trillion-last-year). This speaks to your comment: "Also, considering the extraordinary economic expansion of the last 11 years, from the trough of the Great Recession to today... " When debt is growing faster than GDP, that signals other structural problems, a key one being the lagging growth in net energy. Covid19 threw some unexpected demand destruction into the picture and that may end up being beneficial in the long run. Gramarye also said: "But remember that peak oil is, as the name implies, mostly about oil, which means that electricity generation isn't the big use. " It's an issue when you consider the embedded fossil fuel energy in renewables. Long story short, the issue is more complex than it seems.

-

Peak Oil

The full excerpt on this point: Commodity prices can give misleading signals with regard to future resource abundance. It had been assumed that petroleum depletion would inexorably lead to higher fuel prices. However, since world conventional oil production topped out 15 years ago, prices have seen all-time lows as well as all-time highs. If there is a general price trend at work, it seems to be for oil increasingly to become either too expensive for customers to afford, or too cheap to be profitable for producers. There is no longer a “Goldilocks” price that satisfies everyone. And that’s bad for both the global economy and for oil producers.

-

Peak Oil

Has oil peaked? By Richard Heinberg, originally published by Resilience.org October 8, 2020 https://www.resilience.org/stories/2020-10-08/has-oil-peaked/ A few key excerpts, but lots of good points are made (Note: Resilience only posts Creative Commons content): "Numbers from the US Energy Information Administration’s Monthly Review tell us that world oil production (not counting biofuels and natural gas liquids) actually hit its zenith, so far at least, in November 2018, nearly reaching 84.5 million barrels per day. After that, production rates stalled, then plummeted in response to collapsing demand during the coronavirus pandemic. The current production level stands at about 76 mb/d... "Conventional oil production did plateau starting in 2005 [emphasis added] and oil prices soared in 2007, helping trigger the Great Recession. Afterward, however, there was strong growth in production of >unconventional oil from deepwater wells and Canadian oil sands, and especially from tight oil (also referred to as shale oil) extracted by horizontal drilling and fracking... "After 2010, the focus of the peak oil debate shifted from supply constraints to demand reduction... "In retrospect, by focusing so much on the dynamics of production, peak oil analysts largely failed to elucidate the subtler relationships between oil demand and the larger economy... "Commodity prices can give misleading signals with regard to future resource abundance... "Oil production levels are driven not just by geology and technology, but also by investment—and that adds another source of predictive uncertainty... "Between 30 and 40 small-to-medium-sized oil companies have gone bankrupt since the pandemic began; over a hundred more are teetering on the brink. The Fed has bought up $355 million in oil company debt to stanch the bleeding... "Some commentators suggest that, if the pandemic is resolved soon, planes will resume flying, business will return to normal, and oil demand will hit new highs. That scenario seems unlikely, not only because a full recovery anytime soon is unlikely, but also because oil supply constraints could reinforce demand limits in ways that will be hard for analysts to untangle. For example, the bankruptcy of the shale industry could help precipitate another financial crisis, thereby driving down oil demand. In the subsequent hand-wringing in the financial press, there would likely be relatively little reflection on the role of simple resource depletion in the complex chain of failures and defaults that followed... "The fracking business was always a bubble... "Fracking was an encore for the oil industry’s spectacular performance over the past century-and-a-half. But there isn’t likely to be a second curtain call..."

- Peak Oil

-

Peak Oil

I still wouldn't use the term running out, though. It's about flow rates. Geologists like Ken Deffeyes and the late Colin Campbell, who brought the peak oil discussion to the fore 20 years ago repeatedly said in media interviews that "it's not about running out", but like I said, it never sunk in. A super-giant oil field can produce for a very long time after it's peak. The rub is in the amount it can produce. Perhaps the point is too much on the technical side, but the term "running out" has produced a lot of confusion.